Doing Memory and femicide in public (in)visibility

Tanja Thomas

Despite campaigns such as ‘Orange the World‘ and international protest movements such as ‘Ni Una Menos‘, the public discussion and remembrance of the victims of femicide and violence against women* is often a blind spot: Only in very few places are the victims publicly commemorated; if this happens, it is mostly in the context of action days or on an initiative and through the voluntary efforts of political activists.

This makes Doing Memory of victims of femicide all the more remarkable and important – of individual victims as through the web documentary “Against Us”, which commemorates the murder of Marwa El-Sherbini in 2009 in Dresden, or a public commemoration through appeals as on the International Day against Violence against Women on 25 November 2021. In Tübingen as in other cities, pairs of red shoes stood in public places and told of the lives, experiences and deaths of women as victims of femicide:

For remembering is not only a form of expression of mourning, but also a way to generate public attention, to promote social debates beyond individual blame, to claim political consequences and legal adjustments and to publicly demand and enforce resources for measures in the sense of victim protection, for support structures and prevention.

How the term is understood

‘Femicide’ – this term was first used by the US sociologist Diana Russell in 1976 at the International Tribunal on Crimes against Women. The term, she explains again and again, stands for the “most extreme form of sexist terror” (Caputi/Russell 1992), and she understands it to mean killings out of hatred and contempt for women or because, from the men’s point of view, women* evade patricharchal role expectations, male control and dominance.

Femicides not only denote the most extreme form of violence against women* and girls*, but also represent one of the most violent manifestations of a right-wing ideology of inequality – even if not all perpetrators represent a strict right-wing world-view, anti-feminist world-views are widespread in German majority society; these deny and fight the concepts, resources and rights of women and LGBTIQ+. The term ‘femicide’ is intended to address violence against women* as a structural problem; Liz Kelly already emphasised in 1988 that this extreme form of violence must be seen in the continuum of (everyday) sexism and sexualised violence against women*.

Sexism can therefore be understood as a stabilising resource of patriarchal structures and violence against women*. Sexism should be understood as personal, epistemic/political-cultural, structural as well as institutional forms of negative attributions, attitudes, devaluations and subordinations up to violence against girls* and women*, precisely because they are thought of and constructed as subordinate to men and boys on the basis of ‘gender’ (Leidinger/Thomas 2019). Sexism serves to maintain a patriarchal social order (male supremacy) and promotes hatred and violence, femicide against women*.. The ideology of the inequality of women* is thus supported by socially traditional and globally widespread heterosexist ideas and mechanisms of inequality, which are in many cases structurally and institutionally anchored and are also (re-)produced in media discourses and fictionalisations (Linke/Kasdorf 2021).

Lack of data capture

The complete failure of state authorities to prosecute and punish perpetrators in Mexico was highlighted by Marcela Lagarde (2006), who coined the term ‘Feminicidio’, ‚Feminizid‘ in German: not only did she draw attention to the dramatic increase in extreme violence against women and killings of women, especially in the city of Ciudad Juarez. The term also denounces the murder of women* as a major crime tolerated by public institutions and officials. The use of the term emphasises the need to push for state prosecution of perpetrators also in light of the international accountability of states for human rights violations.

There is no separate criminal classification for femicide in Germany, even though this would be helpful. That is because the existence of the law builds visibility for this specific violence, creates a structure that obliges the state to build up capacity, train the judiciary and the police — for example by setting up specific investigation units and also court departments for femicide as well as developing procedural assistance for victims and other testimony regulations for victim protection. This debate is only making slow progress and is also attracting public attention through committed specialist lawyers such as Christina Clemm and her publications such as “Akteneinsicht, Geschichten von Frauen und Gewalt” (Access to files, stories of women and violence).

Consequences for victim protection, criminal liability and public perception

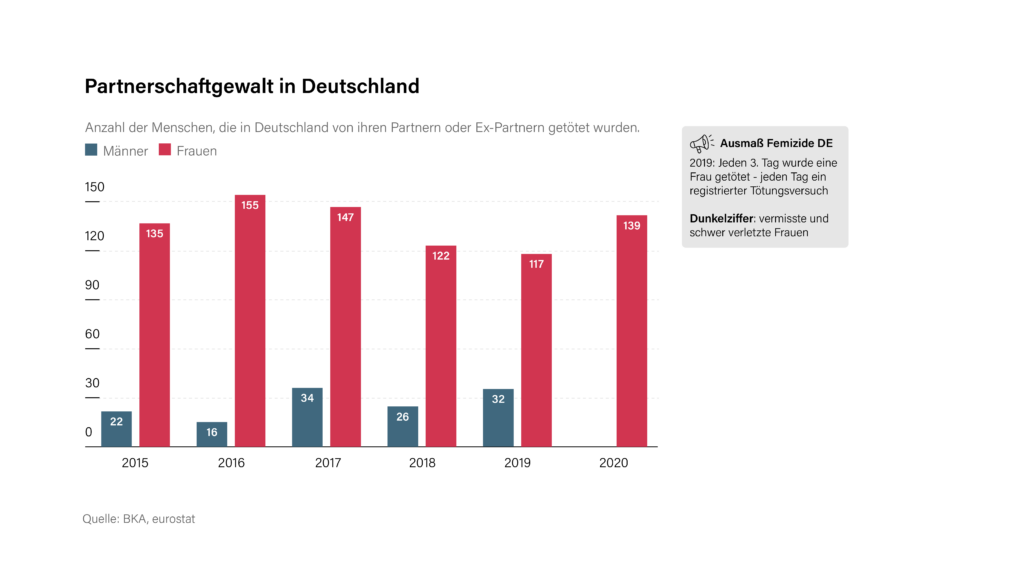

Accordingly, the data on femicides in Germany is still inadequate (cf. the country-specific data compiled by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE)).

In the field of hate crime in general, we can assume that one third of criminal and violent offences are not recorded – we can see this from the surveys of the Criminalistics Institute of the BKA and the LKA Niedersachsen on victimisation and motives compared to the data that victim counselling centres and journalistic research bring to light. ‘Misognyy’ is not a category for the official agencies. And what is even more dramatic: In response to a small question on the incel scene, the federal government stated in 2022 that there is also no intention in the future to include femicides as a separate area of phenomenon and recording category in the police crime statistics (PKS). And that even though we know that criminal prosecution only improves when statistics on the motives for crimes are available. We know that it improves the ability of law enforcement agencies to identify misogyny if they can tick it off as a motive on forms. And we know that this also increases the willingness of those affected to report acts of misogyny.

Heike Kleffner, Director of the Association of Counselling Centres for People Affected by Right-Wing, Racist and Anti-Semitic Violence (in an interview with Tanja Thomas on 17.02.2022)

The willingness and the criteria for recording femicides and the data situation are unclear and this is apparently not to change. The number of unreported cases is high, changes in the number of victims are therefore difficult to interpret, and the justified protection of the victims and their relatives also prevents public discussion.

Moreover, gender-based violence is often played down and taken out of context by the media: As Christine Meltzer (2021) clearly shows in a study on media coverage of violence against women, homicides against women* are indeed portrayed – and here with a special focus on violence carried out by perpetrators described as ‘strangers’, although proportionally this occurs less frequently. Violence between current or former partners, on the other hand, is given relatively little space in the coverage. Although the dpa (German Press Agency) announced in November 2019 that it would refrain from using such terms in future, a murder is still regularly turned into a ‘crime of passion’, a ‘relationship drama’ or a ‘family tragedy’. This choice of words qualifies the acts, implies complicity on the part of the women involved and thus conceals systematic violence against women without shedding light on the structures that link these killings to possessiveness or gender-specific expectations of women’s behaviour. Guidelines for responsible reporting are still very rare.

What is changing in the public perception of victims of misogyny is due to the work of counselling structures and lawyers like Christina Clemm and Asha Hedayati. With regard to the victims of right-wing, anti-Semitic or anti-Muslim misogyny, the public perception is close to zero. Yet women who are recognisable as Muslim women, for example because of their hijabs, are exposed to massive violence, which is also motivated by misogyny. And currently there are misogynistic attacks on journalists in the circles of persons who deny Corona. There is also everyday right-wing violence against women who intervene against misogynist slogans. The dimension of this is not being perceived by the public at all.

Heike Kleffner, Director of the Association of Counselling Centres for People Affected by Right-Wing, Racist and Anti-Semitic Violence (in an interview with Tanja Thomas on 17.02.2022)

Thanks

Special thanks to Heike Kleffner for her willingness to be interviewed and for providing many additional pointers!

Literature

Caputi, Jane/Russell, Diana E.H. (1992): Femicide: Sexist Terrorism against Women. In J. Radford & D.E.H. Russell (eds.), Femicide. The politics of women killing New York: Twayne Publishers, 13-21.

Kelly, Liz (1988): Surviving Sexual Violence. Cambridge: Polity.

Leidinger, Christiane/Thomas, Tanja (2020): Sexismus. (Re)Aktualisierungen und Konjunkturen in der Frauenbewegung, Geschlechterforschung und medialen Öffentlichkeiten. In: dies./Ulla Wischermann (Hg.): Feministische Theorie und Kritische Medienkulturforschung. Ausgangspunkte und Perspektiven. Bielefeld: transcript, 275-292.

Recommendations for further reading

AK Fe.In (2021): „Frauen*rechte und Frauen*hass: Antifeminismus und die Ethnisierung von Gewalt. Berlin: Verbrecher Verlag.

Backes Laura/Margherita Bettoni (2021): Alle drei Tage. Warum Männer Frauen töten und was wir dagegen tun müssen. München: DVA.

Defining und identifying femicide: A literature review.

Lastesis (2021): Verbrennt eure Angst! Ein feministisches Manifest. S. Fischer. For more information or in case you need assistance:

https://www.frauen-gegen-gewalt.de/de/aktuelles.html

Weil Shalva/Consuelo Corradi/Marceline Naudi (eds.)(2018): Femicide across Europe. Theory, research and prevention. University of Bristol: Policy Press, online abrufbar unter library.oapen.org.